AIML Fundamentals

AIML, or Artificial Intelligence Mark-up Language enables people to input knowledge into chatbots.

If you prefer learning by video, check out our free AIML course on Udemy.com or our Office Hours with Steve Worswick on YouTube

AIML, describes a class of data objects called AIML objects and partially describes the behavior of computer programs that process them. AIML objects are made up of units called topics and categories, which contain either parsed or unparsed data.

Parsed data is made up of characters, some of which form character data, and some of which form AIML elements. AIML elements encapsulate the stimulus-response knowledge contained in the document. Character data within these elements is sometimes parsed by an AIML interpreter, and sometimes left unparsed for later processing by a Responder.

CATEGORIES

The basic unit of knowledge in AIML is called a category. Each category consists of an input question, an output answer, and an optional context. The question, or stimulus, is called the pattern. The answer, or response, is called the template. The two primary types of optional context are called “that” and”topic.” The AIML pattern language is simple, consisting only of words, spaces, and wildcard symbols like _ and *. The words may consist of letters and numerals, but no other characters. The pattern language is case invariant. Words are separated by a single space, and the wildcard characters function like words.

The first versions of AIML allowed only one wild card character per pattern. The current AIML standard permits multiple wildcards in each pattern, but the language is designed to be as simple as possible for the task at hand, simpler even than regular expressions. The template is the AIML response or reply. In its simplest form, the template consists of only plain, unmarked text.

More generally, AIML tags transform the reply into a mini computer program which can save data, activate other programs, give conditional responses, and recursively call the pattern matcher to insert the responses from other categories. Most AIML tags in fact belong to this template side sub-language.

AIML 1.x versions supports two ways to interface other languages and systems. The <system> tag executes any program accessible as an operating system shell command, and inserts the results in the reply. Similarly, the <javascript> tag allows arbitrary scripting inside the templates. (Note that Pandorabots supports AIML 2.0, which does not implement these tags.)

The optional context portion of the category consists of two variants, called <that> and <topic>. The <that> tag appears inside the category, and its pattern must match the robot’s last utterance. Remembering one last utterance is important if the chatbot asks a question. The <topic> tag appears outside the category, and collects a group of categories together. The topic may be set inside any template.

AIML is not exactly the same as a simple database of questions and answers. The pattern matching “query” language is much simpler than something like SQL. But a category template may contain the recursive <srai> tag, so that the output depends not only on one matched category, but also any others recursively reached through <srai>.

RECURSION

AIML implements recursion with the <srai> operator. No agreement exists about the meaning of the acronym. The “A.I.” stands for artificial intelligence, but “S.R.” may mean “stimulus-response,” “syntactic rewrite,” “symbolic reduction,” “simple recursion,” or “synonym resolution.” The disagreement over the acronym reflects the variety of applications for <srai> in AIML. Each of these is described in more detail in a subsection below:

- Symbolic Reduction: Reduce complex grammatical forms to simpler ones.

- Divide and Conquer: Split an input into two or more sub-parts, and combine the responses to each.

- Synonyms: Map different ways of saying the same thing to the same reply.

- Spelling or grammar corrections

- Detecting keywords anywhere in the input.

- Conditionals: Certain forms of branching may be implemented with

<srai> - Any combination of (1)-(6)

The danger of <srai> is that it permits the botmaster to create infinite loops. Though posing some risk to novice programmers, including <srai> is much simpler than any of the iterative block structured control tags which might have replaced it.

(1). Symbolic Reduction

Symbolic reduction refers to the process of simplifying complex grammatical forms into simpler ones. Usually, the atomic patterns in categories storing chatbot knowledge are stated in the simplest possible terms, for example we tend to prefer patterns like “WHO IS SOCRATES” to ones like “DO YOU KNOW WHO SOCRATES IS” when storing biographical information about Socrates. The simplest term of expressing the fundamental meaning of an utterance is often also known as the Intent.

Many of the more complex forms reduce to simpler forms using AIML categories designed for symbolic reduction:

<category>

<pattern>DO YOU KNOW WHO * IS</pattern>

<template><srai>WHO IS <star/></srai></template>

</category>

Whatever input matched this pattern, the portion bound to the wildcard * may be inserted into the reply with the markup <star/>. This category reduces any input of the form “Do you know who X is?” to “Who is X?”

(2). Divide and Conquer

Many individual sentences may be reduced to two or more subsentences, and the reply formed by combining the replies to each. A sentence beginning with the word “Yes” for example, if it has more than one word, may be treated as the subsentence “Yes.” plus whatever follows it.

<category>

<pattern>YES *</pattern>

<template><srai>YES</srai><sr/></template>

</category>

The markup <sr/> is simply an abbreviation for <srai><star/></srai>.

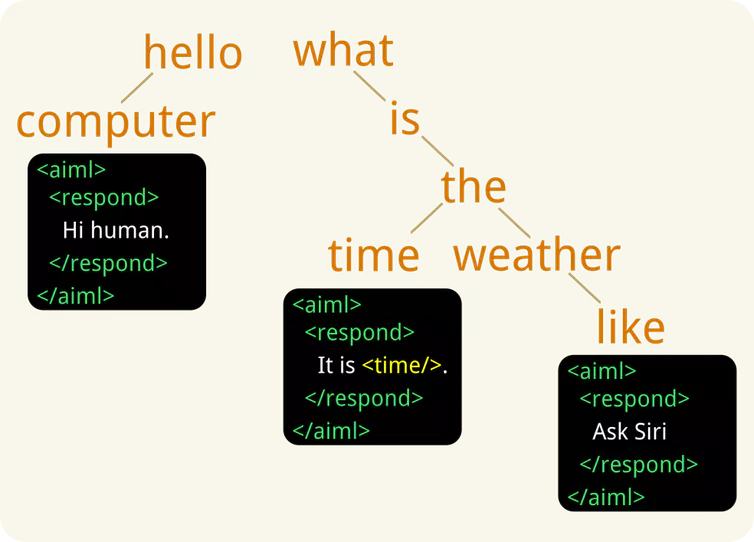

(3). Synonyms

AIML does not permit more than one pattern per category. Synonyms are perhaps the most common application of <srai>. Many ways to say the same thing reduce to one category, which contains the reply:

<category>

<pattern>HELLO</pattern>

<template>Hi there!</template>

</category>

<category>

<pattern>HI</pattern>

<template><srai>HELLO</srai></template>

</category>

<category>

<pattern>HI THERE</pattern>

<template><srai>HELLO</srai></template>

</category>

<category>

<pattern>HOWDY</pattern>

<template><srai>HELLO</srai></template>

</category>

<category>

<pattern>HOLA</pattern>

<template><srai>HELLO</srai></template>

</category>

(4). Spelling and Grammar correction

The single most common client spelling mistake is the use of “your” when “you’re” or “you are” is intended. Not every occurrence of “your” however should be turned into “you’re.” A small amount of grammatical context is usually necessary to catch this error:

<category>

<pattern>YOUR A *</pattern>

<template>I think you mean "you’re" or "you are" not "your."

<srai>YOU ARE A <star/></srai>

</template>

</category>

Here the bot both corrects the client input and acts as a language tutor.

(5). Keywords

Frequently we would like to write an AIML template which is activated by the appearance of a keyword anywhere in the input sentence. The general format of four AIML categories is illustrated by this example borrowed from ELIZA:

<category>

<pattern>MOTHER</pattern>

<template> Tell me more about your family. </template>

</category>

<category>

<pattern>_ MOTHER</pattern>

<template><srai>MOTHER</srai></template>

</category>

<category>

<pattern>MOTHER _</pattern>

<template><srai>MOTHER</srai></template>

</category>

<category>

<pattern>_ MOTHER *</pattern>

<template><srai>MOTHER</srai></template>

</category>

The first category both detects the keyword when it appears by itself, and provides the generic response. The second category detects the keyword as the suffix of a sentence. The third detects it as the prefix of an input sentence, and finally the last category detects the keyword as an infix. Each of the last three categories uses <srai> to link to the first, so that all four cases produce the same reply, but it needs to be written and stored only once.

(6). Conditionals

It is possible to write conditional branches in AIML, using only the <srai> tag. Consider three categories:

<category>

<pattern>WHO IS HE</pattern>

<template><srai>WHOISHE <get name="he"/></srai></template>

</category>

<category>

<pattern>WHOISHE *</pattern>

<template>He is <get name="he"/>.</template>

</category>

<category>

<pattern>WHOISHE UNKNOWN</pattern>

<template>I don’t know who he is.</template>

</category>

Provided that the predicate “he” is initialized to “Unknown,” the categories execute a conditional branch depending on whether “he” has been set. As a convenience to the botmaster, AIML also provides the equivalent function through the <condition> tag.

TARGETING

Robust chabots are created and shaped through a cyclical process of supervised learning called Targeting. Targeting is a cycle incorporating client, bot, and botmaster, wherein client inputs that find no complete match among the categories are logged by the bot and delivered as Targets the botmaster, who then creates suitable responses, starting with the most common queries.

The Targeting cycle produces a progressively more refined bot personality.

The art of AIML writing is most apparent in creating default categories, which provide noncommittal replies to a wide range of inputs. AIML does provide Learning features, as evidenced in the following example dialog:

User: Where do I find the webpage with Australopithecus?

Alice: Where do you want to find it?

User: Bad Answer Alice, time to Learn a new Line

Alice: How would you answer “Where do I find the webpage with Australopithecus?”

User: I would say: “http://www.ancientskulls.net/australopithecus.html”

Alice: Thanks, human. Try asking me again.

User: Where do I find the webpage with Australopithecus?

While crowd-sourced learning is highly appealing, allowing clients to train your chatbot is also highly risky, because there is no way to weed out hackers and trolls who would corrupt the bot by teaching it inappropriate things (as made famous by Microsoft Tay, the unsupervised learning bot who went “bad” on Twitter). Therefore, we suggest restricting the Learn function to a trusted user group or development sandbox.

That is the crux of the learning problem in a nutshell. It all comes down to editing. Either the botmaster edits good quality replies to begin with, or if the bot is “open to the public” then the teacher has to edit out all the crappy answers supplied by all that “free” labor. Compared with a hypothetical learning machine capable of learning language like a child, the AIML targeting approach is more efficient and less risky from the perspective of a brand.

CONTEXT

The keyword “that” in AIML refers to the robot’s previous utterance. Specifically, if the robot responds with a multiple sentence paragraph, the value of that is set to the last sentence in the sequence. The choice of the keyword “that” originated from its use in ordinary language:

R: Today is yesterday.

C: That makes no sense.

R: The answer is 3.1412926 approximately.

C: That is cool.

In AIML the syntax <that>...</that> encloses a pattern that matches the robot’s previous utterance. A common application of <that> is found in yes-no questions:

<category>

<pattern>YES</pattern>

<that>DO YOU LIKE MOVIES</that>

<template>What is your favorite movie?</template>

</category>

This category is activated when the client says YES. The chatbot must determine what they are saying “yes” to. If the chatbot asked, “Do you like movies?,” this category matches, and the response, “What is your favorite movie?,” continues the conversation along the same lines.

Another sample application of <that> are categories that enable the robot to respond to knock-knock jokes:

<category>

<pattern>KNOCK KNOCK</pattern>

<template>Who is there?</template>

</category>

<category>

<pattern>*</pattern>

<that>WHO IS THERE</that>

<template><person/> who?</template>

</category>

<category>

<pattern>*</pattern>

<that>* WHO</that>

<template>Ha ha very funny, <get name="name"/>.</template>

</category>

C: Knock knock.

R: Who’s there?

C: Banana.

R: Banana who?

C: Knock knock.

R: Who’s there?

C: Banana.

R: Banana who?

C: Knock knock.

R: Who’s there?

C: Orange.

R: Orange who?

C: Orange you glad I didn’t say banana.

R: Ha ha very funny, Nancy.

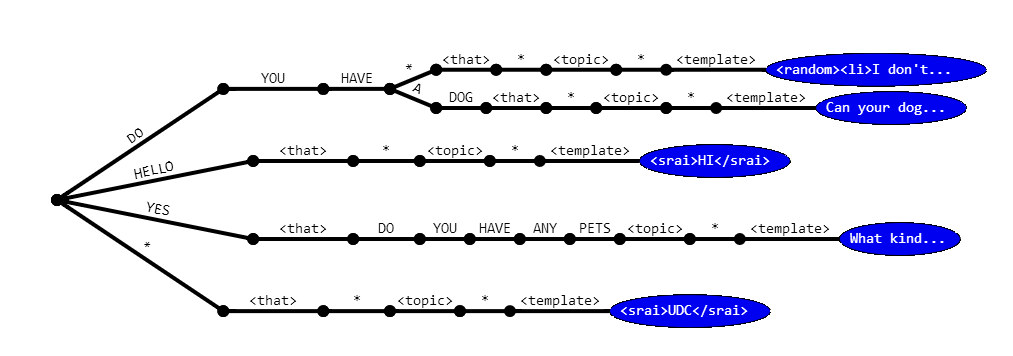

Internally the AIML interpreter stores the input pattern, that pattern and topic pattern along a single path, like: INPUT <that> THAT <topic> TOPIC. When the values of <that> or <topic> are not specified, the program implicitly sets the values of the corresponding THAT or TOPIC pattern to the wildcard *.

The first part of the path to match is the input. If more than one category have the same input pattern, the program may distinguish between them depending on the value of <that>. If two or more categories have the same <pattern> and <that>, the final step is to choose the reply based on the <topic>.

In terms of design, you should never use <that> unless you have written two categories with the same <pattern>, and never use <topic> unless you write two categories with the same <pattern> and <that>. Still, one of the most useful applications for <topic> is to create subject-dependent lines like:

<topic name="CARS">

<category>

<pattern>*</pattern>

<template>

<random>

<li>What’s your favorite car?</li>

<li>What kind of car do you drive?</li>

<li>Do you get a lot of parking tickets?</li>

<li>My favorite car is one with a driver.</li>

</random>

</template>

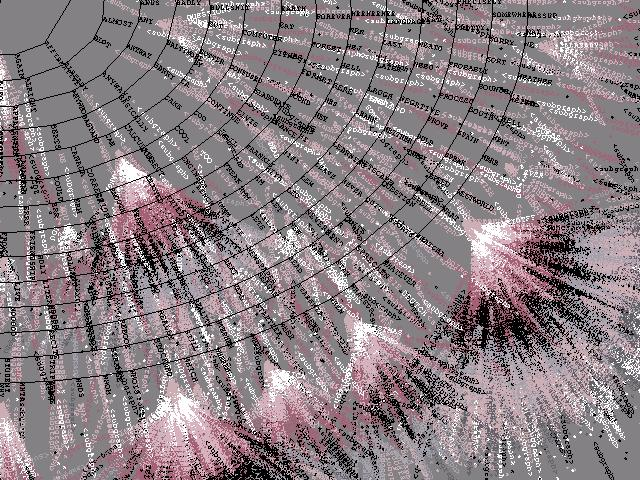

Considering the vast size of the set of things people could say that are grammatically correct or semantically meaningful, the number of things people actually do say is surprisingly small. In his book How the Mind Works, Stephen Pinker wrote:

“Say you have ten choices for the first word to begin a sentence, ten choices for the second word (yielding 100 two-word beginnings), ten choices for the third word (yielding a thousand three-word beginnings), and so on. (Ten is in fact the approximate geometric mean of the number of word choices available at each point in assembling a grammatical and sensible sentence). A little arithmetic shows that the number of sentences of 20 words or less (not an unusual length) is about 1020.”

Fortunately for chat robot programmers, Pinker’s calculations are way off. Our data indicate that the number of choices for the “first word” is more than ten, but it is only about two thousand. Specifically, about 2,000 words cover 95% of all the first words input to bots hosted on Pandorabots. The number of choices for the second word is only about two. To be sure, there are some first words (“I” and “You” for example) that have many possible second words, but the overall average is just under two words. The average branching factor decreases with each successive word.

No other theory of natural language processing can better explain or reproduce the results within our territory. You don’t need a complex theory of learning, neural nets, or cognitive models to explain how to chat within the limits of A.L.I.C.E.’s categories. Our stimulus-response model is as good a theory as any other for these cases, and certainly the simplest. If there is any room left for “higher” natural language theories, it lies outside the map of the A.L.I.C.E. brain.

Academics are fond of concocting riddles and linguistic paradocses that supposedly show how difficult the natural language problem is. “John saw the mountains flying over Zurich” or “Fruit flies like a banana” reveal the ambiguity of language and the limits of an A.L.I.C.E.-style approach (though not these particular examples, of course, A.L.I.C.E. already knows about them). In the years to come we will only advance the frontier further. The basic outline of the spiral graph may look much the same, for we have found all of the “big trees” from “A *” to “YOUR *”. These trees may become bigger, but unless language itself changes we won’t find any more big trees (except of course in foreign languages). The work of those seeking to explain natural language in terms of something more complex than stimulus response will take place beyond our frontier, increasingly in the hinterlands occupied by only the rarest forms of language. Our territory of language already contains the highest population of sentences that people use. Expanding the borders even more we will continue to absorb the stragglers outside, until the very last human critic cannot think of one sentence to “fool” A.L.I.C.E..